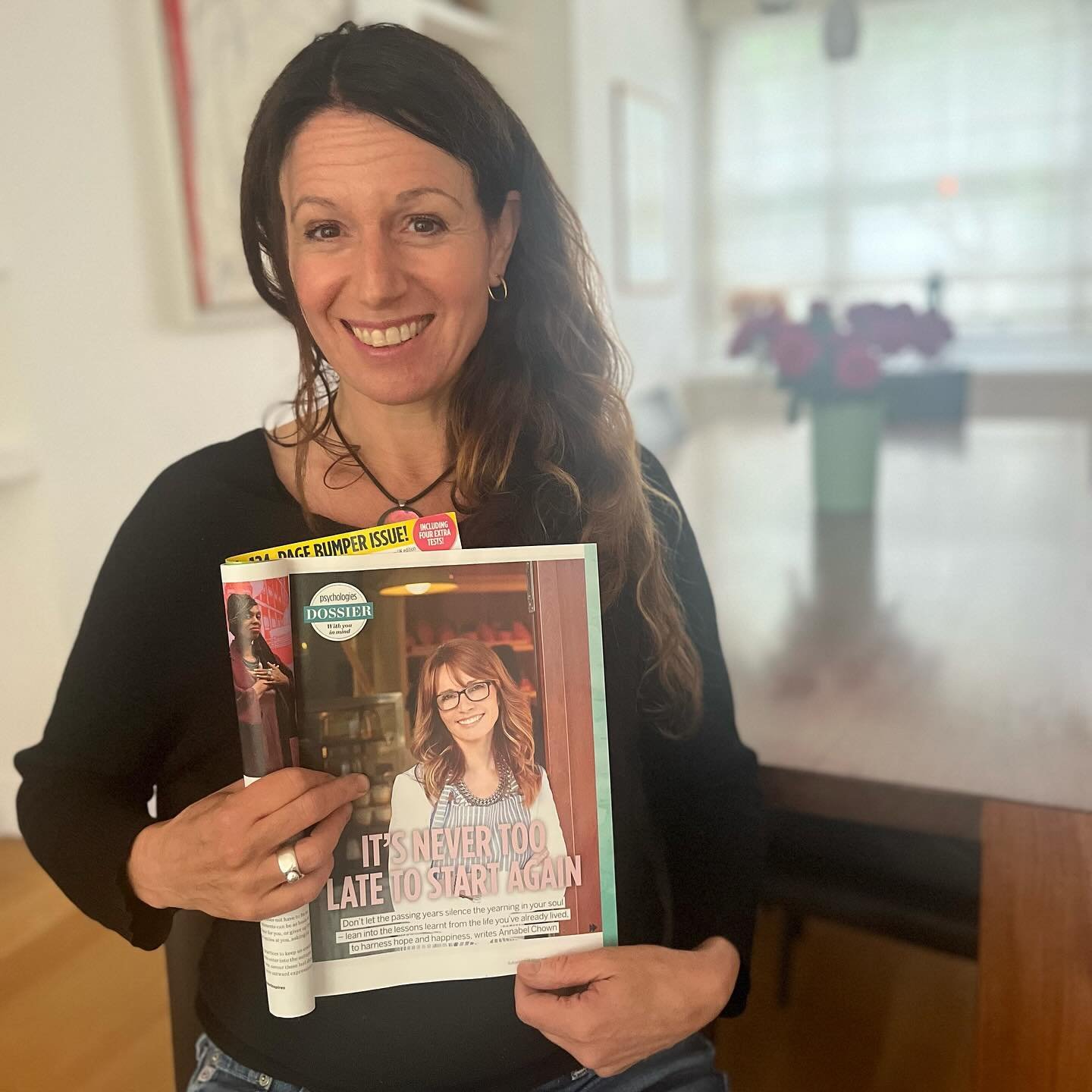

The lessons that cancer taught me by Annabel Chown,

published in The Daily Telegraph, October 26th 2004

I woke up in hospital on a beautiful May afternoon in 2002, aged 31, to be told that the seemingly benign cyst I’d just had removed from my left breast was actually cancer. Twenty-four hours earlier, I had been on holiday in New York, saturating myself in cocktails, pancakes, shopping and art galleries.

Without warning, I was plunged into a world in which I believed I did not belong: sickness, the preserve of others. I had to surrender to scans, X-rays, surgery, silent waiting rooms, results, shock, fear and, finally, a prescription for several months of treatment: chemotherapy followed by radiotherapy.

The familiar slipped away, as I found myself enclosed in the otherworldly sanctuary of illness. It was a strange summer, a curious fusion of glorious liberation from the restrictive routine of work, set against the throb of the chemotherapy and its bequest of violent sickness, baldness and, of course, the constant reminder that I had cancer.

Instead of spending my days sitting on the Tube, staring at a computer screen, eating sandwiches at my desk and seeing only brief glimpses of a concrete-framed blue sky, I spent hours lying on Primrose Hill or in my parents’ garden. The long, hot days of a summer spent outdoors held the forgotten scent of childhood. Except I wasn’t that innocent, blonde-haired child any more. It was luxurious to be able to indulge in decadent pleasures, such as long lunches with friends, afternoon yoga classes and massages, but there was an undercurrent of fear. Despite an apparently good prognosis, suddenly everything seemed fragile.

Inhabiting a very different world to that of my peers, I felt alienated from them. Most of my friends were racing around, frantically busy with careers and partying, or wedding plans and new babies. Meanwhile, I was living in a suspended world, punctuated by hours in the oncology department of my local hospital, where most of the other patients seemed to be middle-aged women. It was humbling, though, to spend time with people who were sick, many of them a lot more so than I was, and to enter a place from which I naively believed myself to be exempt. And to see that, even in advanced stages of illness, life, with its full spectrum of joy, humour, sadness and pain, still carried on; that illness was not the territory of exile I had previously envisaged.

Having cancer when you are young, single and childless brings its own set of issues. Would the treatment leave me infertile? Would anyone every fall in love with me again, or would the cancer scare them away? I was lucky not to have had a mastectomy, but am still self-conscious of my four-inch scar and the story it tells.

During treatment and its aftermath, I completely lost my confidence as a woman although I was constantly complimented on my great new ‘haircut’ (a wig) and chemo-induced size eight body. But I felt unattractive, invisible to men, and believed that the most defining thing about me was my cancer. I felt it had taken over my life, cracked me open, ripped away the veneer by which I had previously defined myself – a successful career as an architect, long hair, a busy social life.

While it would have been nice to have someone tell me that I was still beautiful and lovable, even when bald, sick and pumped full of drugs, it was also liberating not to have a partner. I had no responsibilities, and there was no-one I had to look after. Instead, my parents, sister and friends looked after me. I retreated into my own world, where fears about dying young were juxtaposed with fantasies about what I would do in my magnificent post-cancer life.

As summer faded away, I became weighted down with a leaden exhaustion. The months of treatment started to take their toll – going to the radiotherapy department, day in day out, under an eternally sullen London sky; lying still as the arm of the giant radiotherapy machine traced its arc over my chest and Magic FM played Christmas tunes in the background.

I’d had enough. Yet I was also slightly terrified of returning to the real world, of having to deal with sensible things, such as work and money, and no longer being in this space that was oddly protective and cocooning, where people constantly monitored and looked after me. For cancer had become my own normality.

The end of treatment did not leave me exhilarated. Everyone around me wanted to be reassured that the whole episode was over, the treatment was complete and my recent scans clear. But all I could see was what the cancer had taken away from my life. And I didn’t know how to negotiate the world, as it was not quite the same as the one I had left behind. Or rather, it was the same but I wasn’t. The presence of 12mm of cancer in my body had shifted my parameters and forced me to question who I was and what I wanted from life.

Cancer changes everything and nothing. It was tempting to think that life’s balance sheet would be redressed and everything else in my life would, from then on, be perfect. And that the gratitude I’d initially felt for each day I woke up alive and hopefully cancer-free would last forever. But life carried on and bank queues and Tube delays continued to irritate me.

What cancer has instilled in me, though, is a deeply-held reminder that life is, indeed, precious and fleeting and that it will inevitably contain both joy and sorrow. That there is a wonder in being human, of having been born, having a body, a life, and, of course, a death. And that nothing about the future can be taken for granted. Caught up in the fog of everyday life, it’s easy to forget this.

Before getting ill, I felt as if I was on a constant treadmill, endlessly trying to balance the demands of work and life. The shock of cancer was a catalyst which gave me permission to slow down, to focus more on what actually made me happy rather than what I thought ought to make me happy. And, strangely, to become less averse to risk – after all, the worst things that could happen is I get sick again and die. In light of that, things I have done – going freelance, for example, or travelling alone – seem small in comparison.

But cancer leaves its residues. Although the fear that enveloped me at the start has faded, it remains, deep inside, at times reappearing as raw as ever.

These days, cancer seems to be desperately trying to shed its traditional association with death – Cancer Research UK’s recent radio advertisements had happy-sounding people saying in very relieved voices, ‘And then they told me I was clear’. And breast cancer has had so much media coverage, as well as so many celebrities admitting to having had it, that it seems to have become almost commonplace.

But, just as no-one really knows why I got it in the first place, no-one can be absolutely sure whether or not it will come back. Cancer has been my captor and my liberator, a curse and a gift.